In this three-minute video, learn more about how the Waterfront Botanical Gardens site is a natural extension of Louisville’s deep-rooted history. From 19th century Butchertown to the gardens of today, watch and discover the transformations of this land over the years into the beautiful landmark that it is today.

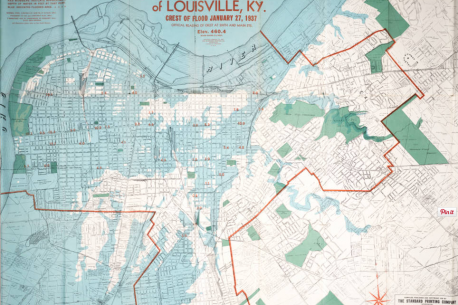

The Waterfront Botanical Gardens site lies within the boundaries of one of Louisville’s oldest city areas, known as “The Point.” In its earliest days, The Point was part of a triangular area of land completely surrounded by water. An 1857 map of the city shows a small grid of streets in the area. Fulton (now River Road), Van Buren, Irvine, Lloyd, and Clinton Streets ran parallel to the Ohio River, and were bisected by Adams, Wayne, Ohio and Marion Streets.

The 1800s

In February, 1883, the Ohio crested at 66-1/2 feet over low water, breaching the levee that protected the city, placing The Point under 30 feet of water.

During the antebellum period, Fulton Street was lined with summer homes of prosperous French families from New Orleans, who came north during the summer months to escape the heat. A house known as “French Garden” was located near where Ohio Street meets River Road, and it was a hotel for New Orleans summer visitors. In addition to fine homes, The Point included a wooded area that was a popular picnic spot for city residents. Floods in Louisville in 1832 and 1845 caused serious damage to houses lying along the Ohio River, destroying many of them. The old channel of the Beargrass Creek was enclosed during the 1850s to create a covered sewer, and the New Cut of Beargrass Creek was dug to divert storm water from the Muddy and Center Forks of Beargrass Creek into the Ohio River two miles upstream from downtown Louisville.

Over time, The Point evolved as a working class neighborhood with a mixture of small factories and mills, frame cottages, and small brick homes. From the 1850 census forward, the area was home to butchers, mill laborers, weavers, and others who worked in area businesses. Shops along what is now Story Avenue served the residents of the area.

In February, 1883, the Ohio crested at 66-1/2 feet over low water, breaching the levee that protected the city, placing The Point under 30 feet of water. A second Ohio Valley flood the following January also damaged the area. In 1907 the area flooded again, followed by a March 1913 flood that led the New York Times to report, “On the Point, where only tops of houses can be seen, the Ohio has done its worst. Occasionally, one of the weather-beaten houses breaks from its moorings and is swept downstream. The river has been full of wreckage for two days. Stables, outhouses, and sometimes small cottages have floated past.”

1937 Flood

The devastation to the area by the 1937 flood was so profound that the City decided to turn part of the area into a city dump for building refuse from flood damaged homes. The 300 and 400 blocks of Ohio Street, bounded by Irvine and Lloyd Streets, became the Ohio Street Dump. As an open dump, the area became home to wild pigs who scavenged the dump for food scraps. In 1938, the city invoked an earlier city law banning free-roaming pigs within the city limits. During World War II, the Ohio Street Dump became a source of income for many residents of the area who would scavenge for recyclable items, selling paper, cloth and metal refuse to recyclers as part of the war effort. In 1942, Mayor Wilson Wyatt went to Washington, DC to obtain funding for participation in the newly-developed federal landfill program, which the city received.

The early materials in the Ohio Street Dump were primarily building refuse from the city’s flood-damaged homes. Prior to the 1960s, trash transported to dumps often contained ash and sometimes hot coals from coal-burning furnaces. The Ohio Street Dump frequently caught fire, smoldering for days on end. While the burning caused air pollution problems at the time, it resulted in lower layers of refuse being burned away. Rodents in dumps often made fighting fires difficult, as they would gnaw through fire hoses. As a result, fires were allowed to burn themselves out.

Recent History

During World War II, the Ohio Street Dump became a source of income for many residents of the area who would scavenge for recyclable items, selling paper, cloth and metal refuse to recyclers as part of the war effort.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, the Ohio Street Dump charged $1.25 a ton to rural communities to accept their refuse. Private dumps sprang up along River Road, and on Cabel Street, in the proximity of the Ohio Street Dump. Individuals who did not want to pay dump fees often dumped appliances and even cars into Beargrass Creek. In 1953, the Ohio Street Dump was expanded, as the demand for garbage disposal increased. And in 1956, the city raised the dumping fee to $1.75 per ton, in an effort to discourage county communities from trucking garbage into the city for disposal. The opening of the city incinerator reduced some of the refuse volume carted to the site. When I-71 was completed in the late 1960s, it passed by the dump, rendering it the gateway to the city. Preparations began for the closing the Ohio Street site. Dirt and rock fill were added to seal the surface of the landfill.

In 1973, with the opening of the Edith Avenue Landfill, the Ohio Street Dump closed. An eight-year, multi-step closing plan was initiated, meeting public health requirements and stringent EPA rules for filling and stabilizing the site. The site has a dirt fill cap approximately 25 feet in depth, covered with grass planting. Ongoing water monitoring of the water quality of Beargrass Creek above and below the site shows the area to be stable with little discernible changes in the water quality as it passes the site location. At that time, the site was a designated Superfund site; however, as of November, 2010 it no longer appears on the National Priorities List.

WHat’s Next?

In 2009, we selected the site as the location for Waterfront Botanical Gardens. After an extensive Title Search, we signed an agreement with Metro Louisville to formally commit to the property. An Environmental Assessment was performed in 2013. The Master Plan for the Gardens was completed in 2014. Fundraising is now underway – help us make the Gardens a reality by becoming a member today.

inspiring visionaries of botanica/waterfront botanical gardens

While the history of the land itself is fascinating, without people to move the project forward, that land would not have grown into what it has today.

In 1999, Helen Harrigan, a member of Botanica at the time, passed away. Soon thereafter, the organization learned that she had left behind a $1.5 million trust for them to build a botanical garden and conservatory in Louisville. While some members of the group felt that the project would be too much to take on, others wanted to see the vision through. Helen’s trust (and trust!) has been an inciting factor in the progress we’ve seen these past couple decades.

In more recent years, Emil and Nancy Graeser were huge supporters of WBG. Their family is too. In fact, we would not have progressed as far as we have today without their support. Sadly, Emil passed away on December 22, 2018, and Nancy passed away on January 5, 2019.

As a child, Emil found an ad for a Bonsai tree in the back of a magazine and sent off for it. He was passionate about Bonsai ever since. A Japanese garden was originally planned for Phase 3 of the project, which will include Bonsai. It has now moved up the timeline to Phase 1D. Emil was delighted to know that his dream of a Bonsai garden in Louisville would one day be realized.

Not only are Emil and Nancy responsible for the funding of the Graeser Family Education Center, they introduced George Duthie to the project when he wanted to honor the memory of his wife, Mary Lee. The Mary Lee Duthie Gardens will surround the Graeser Family Education Center, a wonderful legacy for the families of these two friends.

They were our supporters, cheerleaders, friends, mentors, connectors, advisors, and constant reminders to keep the project moving and to never give up.

awards & recognition

2017 ASLA Professional Awards: Analysis and Planning

2018 Center for Non Profit Excellence: Art of Vision Award

2018 BUSINESS FIRST NON-PROFIT OF THE YEAR FINALIST

2019 US Botanic Garden Exhibit

2019 GLI INC.credible Awards: Non-Profit of the Year

2021 BUSINESS WOMEN FIRST ENTERPRISING WOMEN

2022 BUSINESS FIRST PARTNERS IN PHILANTHROPY NONPROFIT VISIONARY LEADER